Introduction of Parkinson’s Disease:

Table of Contents

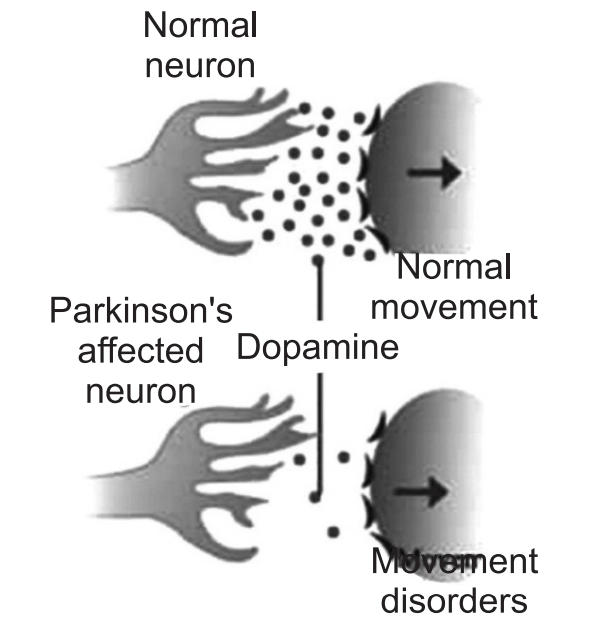

In 1817, British Physician Dr. James Parkinson published a case series describing six patients afflicted with “shaking palsy” (paralysis agitans), a chronic and progressive neurologic disorder called Parkinsonism i.e. loss of control of movement. Parkinson’s occurs when certain nerve cells in a part of the brain called the substantia nigra die or become impaired. Normally, these cells produce a vital chemical known as dopamine. Dopamine allows smooth, coordinated function of the body’s muscles and movement. When approximately 70% of the dopamine-producing cells are damaged, the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease appear. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is recognized as one of the most common neurologic disorders, affecting approximately 1% of individuals older than 60 years. It is a progressive movement disorder marked by tremors, rigidity, slow movement (bradykinesia), and posture instability.

The motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease result from the death of dopamine generating cells in the substantia nigra, a region of the midbrain; the cause of this cell death is unknown. Sometimes it is genetic, but most cases do not seem to run in families. Exposure to chemicals in the environment might play a role.

It usually begins in a person’s late fifties or early sixties. Parkinson’s disease causes a progressive decline in movement controls, affecting the ability to control initiation, speed, and smoothness of motion. Symptoms of Parkinson’s disease are seen in 15% of the people aged 65-74 and almost 30% of people age 75-84.

Most cases of Parkinson’s disease are sporadic. In that, there is a spontaneous and permanent change in nucleotide sequences. Sporadic mutations also involve unknown environmental factors in combination with genetic defects. The abnormal gene (mutated gene) will form an altered end product or protein. This will cause abnormalities in specific areas in the body where the protein is used. Some evidence suggests that the disease is transmitted by autosomal dominant inheritance. This implies that an affected parent has a 50% chance of transmitting the disease to any child.

This type of inheritance is not commonly observed. The most recent evidence is linking Parkinson’s disease with a gene that codes for a protein called α-synuclein.

Causes:

The immediate cause of PD is degeneration of brain cells in the area known as the substantia nigra, one of the movement control centers of the brain. Damage to this area leads to the cluster of symptoms known as “Parkinsonism”.

The substantia nigra is one of the principal movement control centers in the brain. By releasing the neurotransmitter known as dopamine, it helps to refine movement patterns throughout the body. The dopamine released by nerve cells of the substantia nigra stimulates another brain region, the corpus striatum. Without enough dopamine, the corpus striatum cannot control its targets, and so on down the line. Ultimately, the movement patterns of walking, writing, reaching for objects, and other basic programs cannot operate properly and the symptoms of parkinsonism are the result. The cause of Parkinson’s disease is unknown, but several factors appear to play a role, including:

Genetic: Researchers have identified specific genetic mutations such as α–synuclein and parkin, that can cause Parkinson’s disease, but these are uncommon except in rare cases with many family members affected by Parkinson’s disease. Recent studies suggest that dysfunction of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the resultant accumulation of misfolded proteins and endoplasmic reticulum stress may cause the death of Dopaminergic (DA) neurons.

In Parkinson’s disease, degenerating brain cells contain Lewy bodies, which help to identify the disease.

The presence of Lewy bodies: Clumps of specific substances within brain cells are microscopic markers of Parkinson’s disease. These are called Lewy bodies, and researchers believe these Lewy bodies hold an important clue to the cause of Parkinson’s disease.

A synuclein is found within Lewy bodies: Although many substances are found within Lewy bodies, scientists believe the most important of these is the natural and widespread protein called α-synuclein. It is found in all Lewy bodies in a clumped form that cells cannot break down. This is currently an important focus among Parkinson’s disease researchers.

The cell death leading to Parkinsonism may be caused by several conditions, including infection, trauma, and poisoning. Some drugs given for psychosis, such as haloperidol or chlorpromazine, may cause parkinsonism. When no cause for nigral cell degeneration can be found, the disorder is called idiopathic Parkinsonism.

Parkinsonism may be seen in other degenerative conditions, known as the “Parkinsonism plus” syndromes, such as progressive supranuclear palsy.

Some known toxins can cause parkinsonism, most notoriously a chemical called MPTP, (1-methyl-4-phenyl[1]1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine) is a neurotoxin precursor to MPP+, which causes permanent symptoms of Parkinson’s disease by destroying dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of the brain, found as an impurity in some illegal drugs. Parkinsonian symptoms appear within hours of ingestion and are permanent. MPTP may exert its effects through the generation of toxic molecular fragments called free radicals, and reducing free radicals has been a target of several experimental treatments for Parkinson’s disease using antioxidants.

It is possible that early exposure to some unidentified environmental toxin or virus leads to undetected nigral cell death, and manifests as normal age-related decline brings the number of functioning nigral cells below the threshold, needed for normal movement. It is also possible that, for genetic reasons, some people are simply born with fewer cells in their substantia nigra than others, they develop Parkinson’s as a consequence of normal decline.

Risk Factors:

Age: Young adults rarely experience Parkinson’s disease. It ordinarily begins in middle or late life, and the risk increases with age. People usually develop the disease around age 60 or older.

Heredity: Having a close relative with Parkinson’s disease increases the chances to develop the disease. However, risks are still small unless many relatives in a family with Parkinson’s disease.

Sex: Men are more likely to develop Parkinson’s disease than are women.

Exposure to toxins: Ongoing exposure to herbicides and pesticides may slightly increase the risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Pathophysiology:

No specific, standard criteria exist for the neuropathologic diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease, as the specificity and sensitivity of its characteristic findings have not been established. However, the following are the 2 major neuropathologic findings in Parkinson:

- Loss of pigmented dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta.

- The presence of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites.

The loss of dopamine neurons occurs most prominently in the ventral lateral substantia nigra. Approximately 60-80% of dopaminergic neurons are lost before the motor signs of Parkinson’s disease emerge.

Some individuals who were thought to be normal neurologically at the time of their deaths are found to have Lewy bodies on autopsy examination. These incidental Lewy bodies have been hypothesized to represent the presymptomatic phase of Parkinson’s disease. The prevalence of incidental Lewy bodies increases with age. Nonetheless, they are a characteristic pathology finding of Parkinson’s disease.

Symptoms:

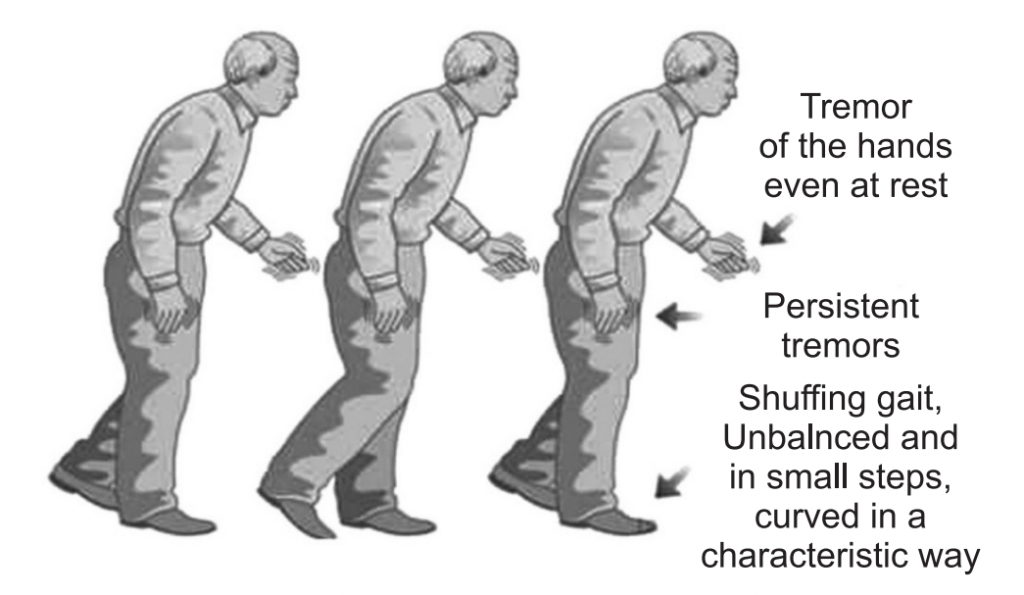

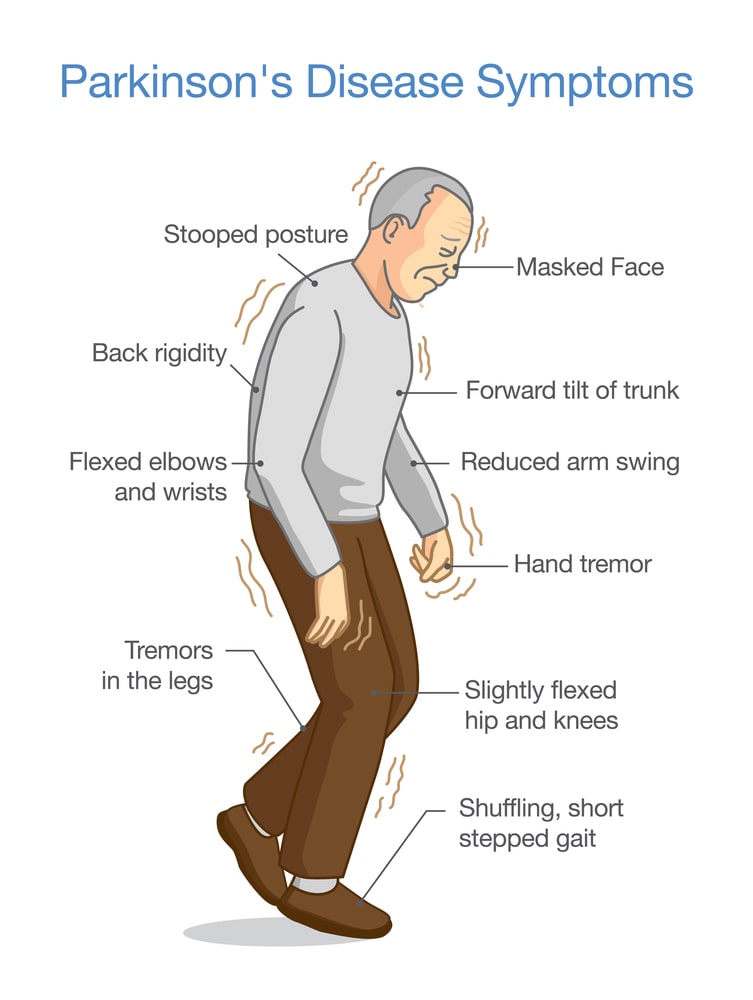

Symptoms and signs may vary from person to person. Early signs may be mild and may go unnoticed. Symptoms often begin on one side of the body and usually remain worse on that side, even after symptoms begin to affect both sides.

Parkinson’s signs and symptoms may include:

Tremors: Usually begins in a limb, often hand or fingers. The classic tremor of Parkinson’s disease is called a “Pill-rolling tremor” because the movement resembles rolling a pill between the thumb and forefinger. This tremor occurs at a frequency of about three per second.

Slowed movement (Bradykinesia): It may involve slowing down or stopping in the middle of familiar tasks such as walking, eating, or shaving, this may include freezing in place during movements (akinesia).

Rigid muscle: Muscle rigidity or stiffness, occurring with jerky movements replacing smooth motion. The stiff muscles can limit the range of motion and cause pain.

Impaired posture and balance: Postural instability or balance difficulty occurs. This may lead to a rapid, shuffling gait (festination) to prevent falling.

Loss of automatic movements: In Parkinson’s disease, the ability to perform unconscious movements, including blinking, smiling, or swinging arms when walking may decrease. In most cases, there is a “masked face”, with little facial expression and decreased eye blinking.

Speech changes: Speech may be more of a monotone rather than with the usual inflections. The patient may speak softly, quickly, slur, or hesitate before talking.

Writing changes: Handwriting changes, with letters becoming smaller across the page (micrographia) and become difficult. Progressive problems with intellectual function (dementia).

Bladder problems: Parkinson’s disease may cause bladder problems, including being unable to control urine or having difficulty urinating.

Constipation: Many people with Parkinson’s disease develop constipation, mainly due to a slower digestive tract.

Smell dysfunction: Problems with the sense of smell, may have difficulty identifying certain odors or the difference between odors.

Fatigue: Many people with Parkinson’s disease lose energy and experience fatigue, and the cause is not always known.

Pain: Many people with Parkinson’s disease experience pain, either in specific areas of their bodies or throughout their bodies.

Sexual dysfunction: Some people with Parkinson’s disease notice a decrease in sexual desire or performance.

In addition, a wide range of other symptoms may often be seen, some beginning earlier than others: Depression, problems with sleep, including restlessness, and nightmares. Emotional changes including fear, irritability, and insecurity.

Tests and Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease involves a careful medical history and a neurological exam to look for characteristic symptoms.

There are no definitive tests for Parkinson’s disease, although a variety of lab tests may be done to rule out other causes of symptoms, especially if only some of the identifying symptoms are present.

Tests for other causes of Parkinsonism may include brain scans, blood tests, lumbar punctures, and X-rays.

Treatment and Drugs:

No known treatment can stop or reverse the breakdown of nerve cells that causes Parkinson’s disease. But many treatments can help your symptoms and improve your quality of life. Treatments for Parkinson’s include:

Medicines: Medicines, such as levodopa and dopamine agonists. The goal is to correct the shortage of the brain chemical dopamine, which causes the symptoms of Parkinson’s. Several medicines that may be used at different stages of the disease are:

- Levodopa and carbidopa: Levodopa is precursor of dopamine. Levodopa is combined with carbidopa, which protects levodopa from premature conversion to dopamine outside the brain, which prevents or lessens side effects such as nausea. L-dopa therapy usually remains effective for five years, as the disease progresses, many patients develop motor fluctuations including dyskinesias (abnormal movements such as twisting, restlessness), rapid loss of response after dosing (“on-off phenomenon) even after taking high doses of levodopa.

- Dopamine agonists (for example, pramipexole or ropinirole): Dopamine agonists may be used before L-dopa therapy or added on to avoid requirements for higher L-dopa doses late in the disease.

- COMT inhibitors: Entacapone and tolcapone are inhibitors of another enzyme system called catechol-o-methyl transferase are effectively treating Parkinson’s disease. This medication mildly prolongs the effect of levodopa therapy by blocking an enzyme that breaks down dopamine.

- MAO-B inhibitors (rasagiline, selegiline): These can prevent the breakdown of brain dopamine by inhibiting the brain enzyme monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) and prolong the effects of dopamine. This enzyme metabolizes brain dopamine.

- Amantadine: Amantadine is sometimes used alone to provide short-term relief of symptoms of mild, early-stage Parkinson’s disease. It may also be given with carbidopa-levodopa therapy during the later stages of Parkinson’s disease to control involuntary movements (dyskinesias) induced by carbidopa-levodopa.

- Anticholinergic agents: These medications were used for many years to help control the tremor associated with Parkinson’s disease. Example: Benztropine or Trihexyphenidyl.

- Apomorphine: A short-acting injectable dopamine agonist, apomorphine is used for quick relief.

- Home treatment: Many steps can be taken at home to make dealing with the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease easier, such as getting regular exercise and eating a healthy diet including plenty of fruits, vegetables, grains, cereals, legumes, poultry, fish, lean meats, and low-fat dairy products.

- Surgery: Brain surgery, for example, deep brain stimulation (DBS), may be considered when medicine fails to control symptoms of Parkinson’s disease or causes severe or disabling side effects.

- Speech therapy: Speech therapists use breathing and speech exercises to help overcome the soft, imprecise speech and monotone voice that develop in advanced Parkinson’s disease.

- Physical therapy and Occupational therapy: Therapists may help improve walking and reduce the risk of falling.

Alternative Treatment:

Alternative therapies, including acupuncture, massage, and yoga can help relieve some symptoms of the disease and loosen tight muscles. Alternative treatment also includes herbal and dietary therapies, including amino acid supplementation, antioxidant (vitamins A, C, E, selenium, and zinc) therapy, B vitamin supplementation, and calcium and magnesium supplementation to treat disease.

Prevention:

Because the cause of Parkinson’s is unknown, there is no known way to prevent Parkinson’s disease. However, some research has shown that caffeine found in coffee, tea, and cola may reduce the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. Green tea also may reduce the risk of developing Parkinson’s. Some research has shown that regular aerobic exercise may reduce the risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Make sure you also check our other amazing Article on : Epilepsy